January 09, 2026

By Leticia Doormann

Indigenous solutions show that land demarcation, traditional knowledge, and territorial care are effective responses to the climate crisis.

Ten years have passed since the adoption of the Paris Agreement at COP21. A decade later, Belém, with the smell of rain and the taste of jambu, promised to be a historic COP30. Some announced it as the COP of forests; others, as the COP of implementation; the most enthusiastic began to call it the Indigenous COP.

However, while the enthusiasm is contagious, the truth is that climate negotiations seem to follow a familiar script: small victories, major omissions, and a multilateral system that still struggles — or shows little willingness — to drive real and sustainable solutions in the long term.

Even so, something awakened in Belém. As much as the air conditioning in the meeting rooms tried to cool territorial voices, and as much as the merchandising of “conscious” brands sought to divert attention, it was the streets, rivers, homes, and camps that reminded us, with the force of the obvious, who is in fact driving an inclusive and resilient climate transition.

In 2015, the world applauded the Paris Agreement. With atmospheric concentration hovering around 400 ppm of CO₂ — far from the 350 ppm recommended by science — the need for change seemed inevitable. The COP21 agreement was received with optimism: limiting global warming to 1.5°C sounded possible; transforming the economy, necessary; climate justice, urgent.

At that moment, Indigenous presence in these spaces was discreet, almost as if it had to carve out room amid so much protocol. The Global Alliance of Territorial Communities, a global coalition of tropical forest peoples, was then taking its first strokes on the international climate stage and brought the Paddling to Paris campaign to the Seine River. A small delegation, a political coordination still under construction, but systemic and profound demands were beginning to resonate.

Some of them were recorded, quite literally, on a paddle handed to Christiana Figueres, then Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC): land demarcation; recognition of traditional knowledge; direct territorial financing; respect for free, prior, and informed consent; and the basic right not to be killed for defending the environment. Five messages, five solutions to the climate crisis.

Ten years later, amid trial and error, this was not enough to curb global warming nor its main drivers: fossil fuel consumption and deforestation. Alongside the rise in meat and hydrocarbon consumption, atmospheric CO₂ continued to increase, and by the time Belém hosted COP30, levels were already approaching 460 ppm.

Alongside the upward curve of temperature and CO₂, another curve grew — far more promising: that of Indigenous, territorial, and community participation in climate negotiation and justice spaces. With it, global alliances and political coordination were strengthened, technical capacity to navigate acronyms and mechanisms increased, and, above all, the ability to present proven and scalable territorial solutions to address the climate crisis expanded.

Thus, over the past decade, a different narrative managed to gain ground: the idea that the response does not lie in technocratic discourse nor in green capitalism, but in territories, in nature, in the communities that sustain them, and in their messages and solutions. Along this same path, economic degrowth emerged to challenge decisions that no longer withstand much logic — something that Indigenous Peoples and local communities have practiced for generations without needing to name it: not extracting more than nature can regenerate, not consuming beyond what is essential, and not confusing well-being with the accumulation of resources.

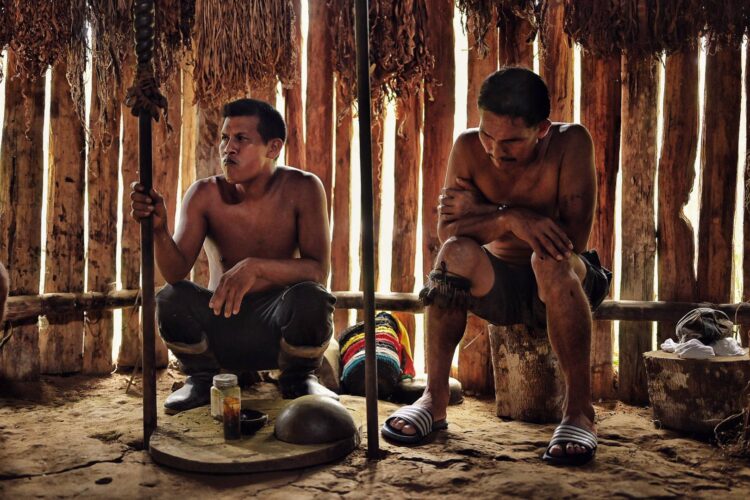

After a year marked by unprecedented political coordination and significant growth in scientific evidence on the role of Indigenous Peoples in forest conservation, the arrival of 5,000 Indigenous leaders from around the world — alongside hundreds of quilombolas — in Belém made it impossible to continue ignoring these voices. This is not just discourse: there is evidence that the demarcation of Indigenous territories could prevent up to 20% of additional deforestation and reduce carbon emissions by 26% by 2030. The demarcation of traditional community lands has been consolidated as one of the most effective tools to contain deforestation, while Indigenous Nationally Determined Contributions (Indigenous NDCs), developed by territorial organizations themselves, have outlined transition pathways without oil or mining in forests, based on the full recognition of territorial rights.

The message is clear: the titling of Indigenous, quilombola, and community lands is a real solution to the climate crisis. Civil society not only followed this progress but also amplified and defended territorial messages. And Brazil took steps that, just a few years ago, seemed unlikely at an event of this scale: 28 quilombos were recognized, taking a decisive step toward the titling of their territories, and 14 new Indigenous territories were demarcated, encompassing different peoples, biomes, and regions.

Indigenous Peoples, Afro-descendant peoples, and local communities continue to offer the same solution they have always offered — and that continues to work: traditional knowledge that respects the environment, territorial governance based on care, and a deep understanding of the limits of nature and of our relationship with it.

Perhaps the secret does not lie in novelty, but in finally listening to those who have long been pointing the way. If Indigenous Peoples protect more than one third of the forests that still remain standing, and if rivers and seas with community guardians preserve biodiversity better and are more resilient to climate change, then the so-called just transition may have less to do with inventing new mechanisms and more to do with reducing global production and consumption, restoring a logic of circularity and care, and transferring power, rights, and resources to those who are on the frontlines of climate action. Perhaps, if we begin to listen now, we can avoid another ten years rehearsing complex solutions while continuing to ignore the most just, sustainable, and resilient ones.

Leticia Doormann is a socioecology specialist and Executive Director of TINTA (The Invisible Thread), a global facilitation platform dedicated to strengthening the efforts of Indigenous Peoples and community organizations in protecting territories and advancing climate action.

This article was originally published by Mídia Ninja. You can read the original version in Portuguese here.